- Obituaries

A risk-taking and highly principled journalist, Whittam Smith helped fund Britain’s first new broadsheet newspaper in more than a century – before successfully stewarding the Church of England through the credit crunch. Sean O’Grady remembers him

Sunday 30 November 2025 18:34 GMTComments

CloseAmol Rajan and Andreas Whittam Smith discuss whether British politics is ‘broken’

CloseAmol Rajan and Andreas Whittam Smith discuss whether British politics is ‘broken’

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails

Email*SIGN UP

Email*SIGN UPI would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our Privacy notice

Andreas Whittam Smith was a gambler – and the biggest risk he ever took was launching The Independent.

Admittedly, gambling is not the first thing that comes to mind when surveying his long and storied career – careers, in truth, such was the variety of roles he took up.

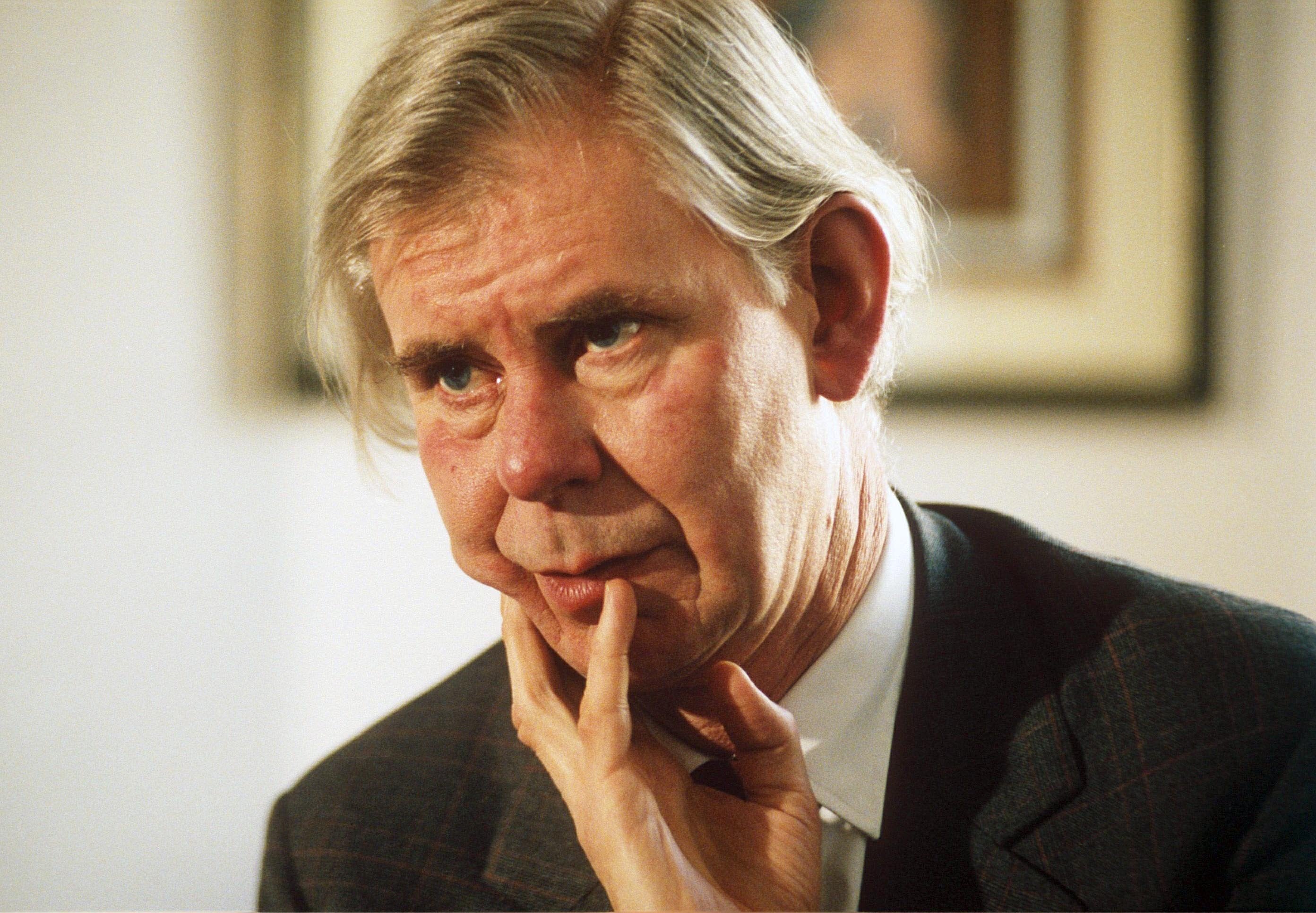

Nor did his famously serene bearing suggest a man given to living on the edge. One former colleague offered this portrait of his distinctive demeanour: “He appeared to glide down Fleet Street with the dignity of a great old battleship, as though his unbending legs were being propelled along the surface of water by some hidden motor. Once, with a sudden graceful movement calculated not to undermine the impression of a stately progress, he rose an inch or two onto the platform of a slowly moving bus.”

Tall, with a gentle manner and a shy smile, he was routinely dubbed “saintly” or “ecclesiastical” and likened to a bishop rather than a bookie. Yet the deed that became his most abiding legacy – the launch of The Independent in October 1986 – was built on his understanding, and taste for, financial risk. It paid off, and... well, as was once said of Sir Christopher Wren, si monumentum requiris, circumspice.

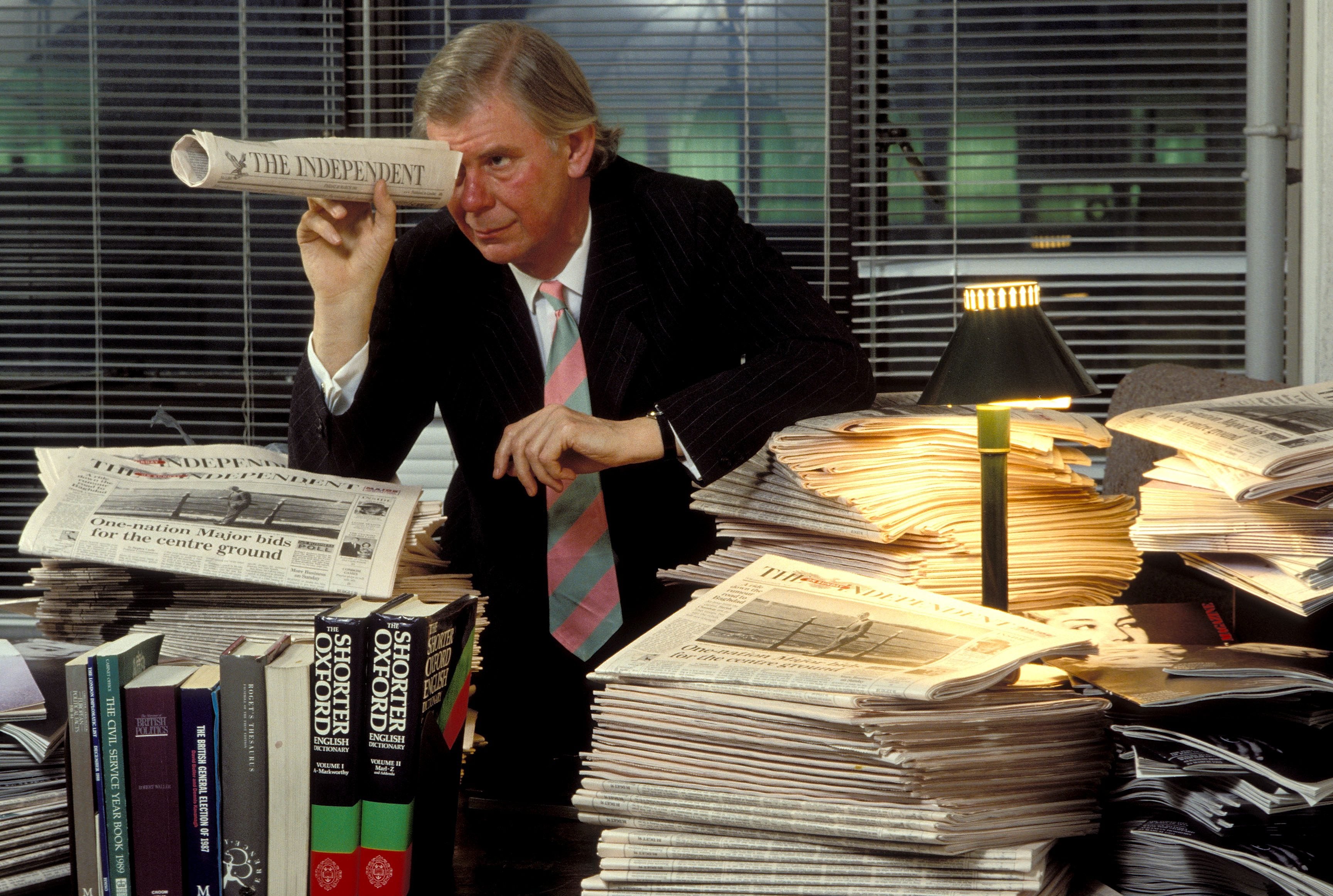

In 1985, Whittam Smith – together with Stephen Glover and Matthew Symonds, two younger and similarly risk-friendly journalists with whom he had worked at The Daily Telegraph – made an “all or nothing” move: to embark on the great adventure of conceiving, funding and producing the first new broadsheet in more than a century.

open image in galleryIn 1985, Whittam Smith made an “all or nothing” move: to embark on the great adventure of conceiving, funding and producing the first new broadsheet in more than a century (Herbie Knott/Shutterstock)

open image in galleryIn 1985, Whittam Smith made an “all or nothing” move: to embark on the great adventure of conceiving, funding and producing the first new broadsheet in more than a century (Herbie Knott/Shutterstock)He once told Charles Wintour, another distinguished editor, about the genesis of The Independent – and the anecdote, as recalled by Wintour, conjures up for us Whittam Smith’s quick and agile mind.

“One of the many ways in which Eddy Shah [who had just launched the mid-market Today] helped to change Fleet Street was to provide the initial inspiration for the launch of The Independent.

“When Shah made the announcement about his new daily in February 1985, the American publication Business Week asked Andreas Whittam Smith, then City editor of The Daily Telegraph, for his comments. He rubbished the whole idea and said it could not possibly succeed.

“No sooner had he put the phone down, he told me later, than he realised he was wrong. He telephoned Shah who, typically, was extremely helpful, then and later.”

It was quite the project – and Whittam Smith knew exactly what he was doing with this calculated risk.

Whittam Smith had taken a keen interest in money ever since he was tasked with counting the change given during the collection at the various parishes served by his father, an Anglican vicar in the northwest of England. He prided himself on being one of the first boys in the country to study what was then the highly novel A-level in economics, in the early 1950s.

open image in galleryAfter leaving Oxford in 1960, he took a post with the prestigious merchant bank NM Rothschild (John Lawrence)

open image in galleryAfter leaving Oxford in 1960, he took a post with the prestigious merchant bank NM Rothschild (John Lawrence)After leaving Oxford in 1960, he took a post with the prestigious merchant bank NM Rothschild, and after two years there switched to writing and made a rapid progression through financial journalism. It was a classic “Fleet Street” career, displaying perhaps also a certain impatient ambition and an eye for the main chance: the Stock Exchange Gazette (1962-63), the Financial Times (1963-64), The Times (1964-66), deputy City editor at The Daily Telegraph (1966-69), City editor at The Guardian (1969-70); editor, Investors Chronicle and Stock Exchange Gazette and director of Throgmorton Publications (1970-77), and then City editor at The Daily Telegraph (1977-85).

The many contacts he accumulated over this time served him well when he was raising finance for the new paper. Based not on a promising idea and a plan but on sheer force of personality, the founders raised a remarkable £21m – some £64m at today’s prices. Before that, and to show willing, Whittam Smith had to mortgage his own home up to the hilt to pay for suitable offices on City Road in Islington, north London.

It was an interesting choice for a base and, like much else about the new paper, carried a certain personal stamp; idiosyncrasies in style and substance that Whittam Smith used to characterise as “classic, with a twist”.

City Road was a symbolic move away from both Fleet Street and the new media bases in London’s Docklands. The Independent was to be the first newspaper to have no permanent allegiance to any political party, which reflected the fact that its founding editor had previously voted for each of the three main parties. It was to be economically and socially liberal, just as he was – a trait that was most dramatically evident in his later role as a reforming and permissive chief censor and president at the British Board of Film Classification.

Whittam Smith was no Thatcherite, but was not ideologically opposed to her free-market reforms; indeed, The Independent could not have been born without the reforms to the trade unions that she imposed.

open image in gallery(Getty)

open image in gallery(Getty)By common consent, it was its first editor who ensured that The Independent was a quality product, noted for its comprehensive foreign and financial coverage as well as its imaginative use of unconventional, striking photography. For example, to mark the opening of the M25, Whittam Smith suggested running a satellite image of the London orbital motorway. He ruled that obituaries should proudly carry the name of their author, and permitted more “attitude” – a minor revolution that helped turn that branch of the trade into an unlikely source of entertainment.

While he insisted on “sparkling” copy, colleagues noted that he also had a high pain threshold for earnestness. Not for nothing was Whittam Smith’s Independent soon nicknamed “the Indescribablyboring” by Private Eye – a backhanded, but nonetheless high, compliment. Less apparent is why the satirists took to calling him “Strobes”, but it stuck.

open image in galleryInfamously, he banned travel assignments involving free hotel stays, and the fashion desk from receiving gifts, insisting that the paper must “pay its way” (Gamma-Rapho/Getty)

open image in galleryInfamously, he banned travel assignments involving free hotel stays, and the fashion desk from receiving gifts, insisting that the paper must “pay its way” (Gamma-Rapho/Getty)Infamously, he banned travel assignments involving free hotel stays, and the fashion desk from receiving gifts, insisting that the paper must “pay its way” – a regime that largely failed to survive the test of time. Suspicious of the establishment, despite amply qualifying for senior membership, he also took The Independent’s Westminster staff out of the secretive lobby system. Like most editors, he abhorred literals (typographical errors), though to an unusual degree; the phrase “of course” was banned. Unlike most editors, he could not stand journalists fiddling their expenses.

In due course (rather than “of course”), Whittam Smith’s audacious move turned him into a very wealthy man, but he never gave the impression that this was his primary motive. He was certainly frustrated at the shortcomings of the Telegraph, and, although often spoken of as a potential successor to its editor Bill Deedes, he was unconvinced that the financially troubled and chronically inefficient title was what he needed, or even that it needed him.

When he got the chance to outline to the then proprietor, Lord Hartwell, the reforms he felt the venerable institution required, he effectively sacked himself before he had to admit that the rumours of his imminent defection were true. Deedes himself later put it in perspective: “There might have been better ways of doing it, but in seeking to escape from what must have seemed to someone close to the City an impenetrable madhouse, run by geriatrics like myself, Whittam Smith had his reasons.”

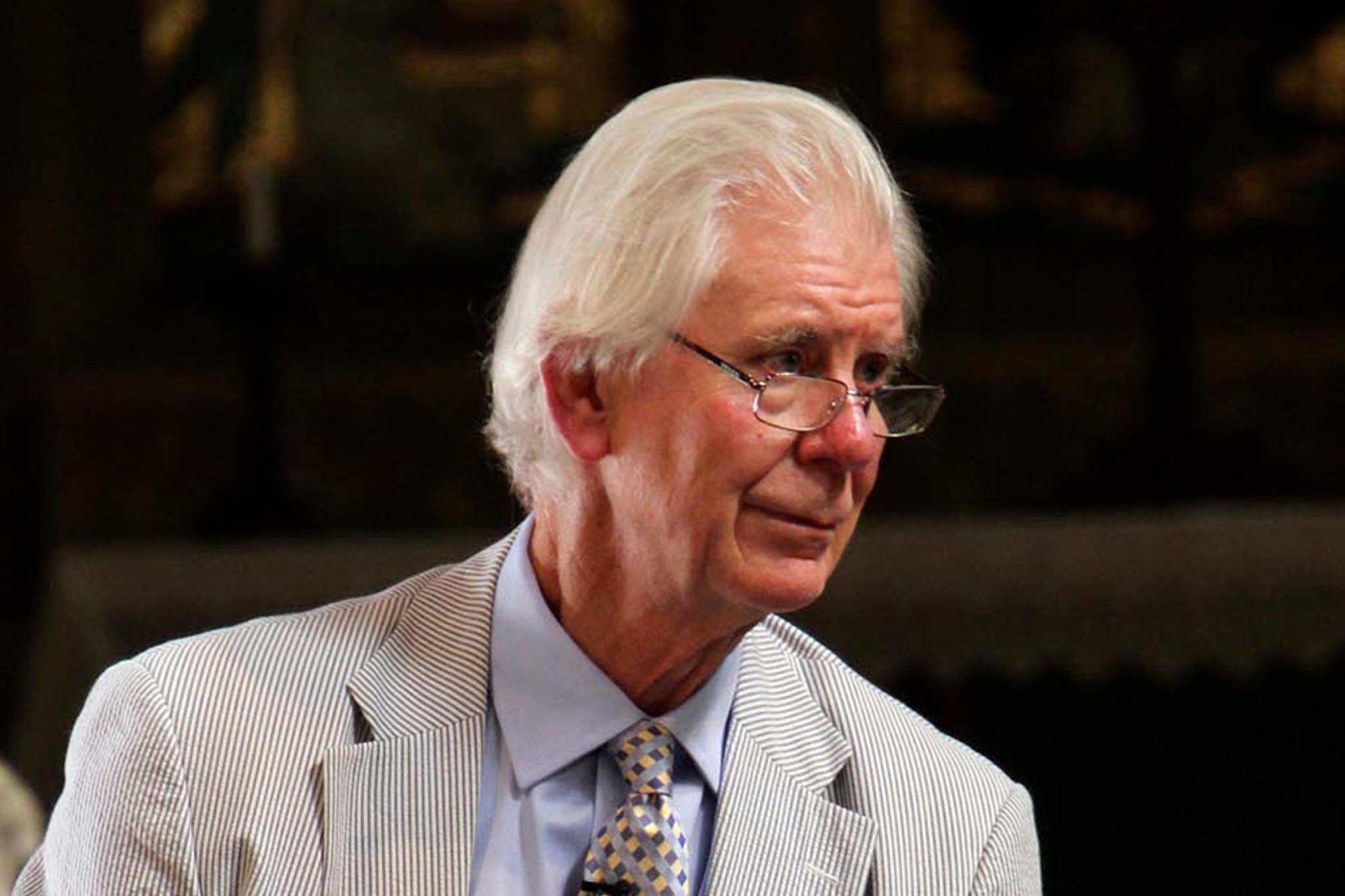

open image in galleryHe spent far longer as the First Church Estates Commissioner, the senior lay member of the Church of England, in which role he also looked after the Church’s portfolio of investments, worth around £8bn (Times Newspapers/Shutterstock)

open image in galleryHe spent far longer as the First Church Estates Commissioner, the senior lay member of the Church of England, in which role he also looked after the Church’s portfolio of investments, worth around £8bn (Times Newspapers/Shutterstock)At 49, Whittam Smith had made publishing history, but his eight-year stint at the helm of The Independent lasted only until 1994, when financial difficulties (ironically enough) and editorial pressures led to his departure.

He spent far longer as the First Church Estates Commissioner, the senior lay member of the Church of England, in which role he also looked after the Church’s portfolio of investments, worth around £8bn. He was an unalloyed success there, which suggests that if he’d stayed with Rothschilds and got to the top of fund management, he’d have grown spectacularly rich.

When he retired after 15 years in 2017, aged 80, he had, possibly with divine intercession, protected the earthly assets of the Church through the global financial crisis, achieving an average return of 6 per cent per annum ahead of inflation. To double the asset base in such a short time required a certain singlemindedness, and Whittam Smith bruised some episcopal egos: his ideas were denounced in a synodical debate by the then Bishop of St Albans as “brutality with a smirk”. Sounds about right.

He was also fond of quoting General Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, a former chief of the German general staff, who had his officers divided into four groups – the clever, the diligent, the stupid and the lazy – and asserted that the most dangerous hybrid was the “diligent, stupid” type.

Understandably, Whittam Smith’s work for the Church receives only a tiny proportion of the coverage devoted to the creation of The Independent, but it is right to point out that had he been less astute and conscientious – attracted to “synthetic bonds” and the like – he’d be bitterly blamed for leaving the established Church busted and broken. His judgement in respect of the trade-off between risk and reward was demonstrably shrewd.

It is perhaps tempting to think he had the most fun as chief film censor, but he found no great enjoyment in the thousands of adult movies he was required to sit through. He had a certain grudging respect, however, for the various porn barons he encountered, maybe seeing in them men who could spot an opportunity to turn a profit: “I said to them, ‘This “office tart” movie... it’s got no artistic merit whatsoever, has it? It’s not meant for anything other than sheer titillation, is it?’ They said, ‘No, that’s right.’

“I immediately thought to myself, ‘I can work with these people.’ What I liked about them is that they had absolutely no cant. That seemed so refreshing.”

Whittam Smith’s main achievement in this role was in finally allowing A Clockwork Orange, The Exorcist and other classics to be released on video. He even suggested that, one day, film classifications would disappear; he always was socially liberal.

He was knighted in 2015 (“for public service, particularly to the Church of England”), and his double-barrelled (but not hyphenated) name, as well as his ways, often led people to think he had come from some greatly privileged background. He had not. He was known at school as “Andy Smith”, and somewhere along the line, the embellishments were added. He was, strictly, a scouser, growing up in Birkenhead with his father, Canon JE Smith, and mother.

open image in gallery(PA)

open image in gallery(PA)Whittam Smith described his background – Birkenhead School (a direct grant establishment) and Keble College, Oxford – as follows: “I had a good education, but not one that could be described as elitist in a social sense. It wasn’t Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, nor Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge... There was nothing pukka about the school: the social mix stretched from dockers’ sons to doctors’ sons.”

He studied philosophy, politics and economics, achieving a third-class degree. He was so ashamed of this that he didn’t go to the graduation ceremony – until long after, when Keble made him an honourary fellow and he was obliged to.

That was after he’d finished his national service, in the infantry. Interestingly, Whittam Smith once remarked that he’d been posted to Spandau Prison in Germany, as a guard. Given that Spandau’s most famous inmate was Rudolf Hess, former deputy fuhrer to Adolf Hitler, it’s possible that the young Andreas missed out on an interesting interview opportunity. But, then, he showed no interest in journalism until well after he had left university.

Whittam Smith’s greatest failures were both poignant and heroic. Twice in the politically dismal decade of the 2010s, he attempted to launch citizen-based political parties, rightly discerning a growing disillusionment among voters with the electoral system. The proposal was for a citizens’ assembly to rewrite the constitution. Unfortunately, the gap in the market he identified for “Democracy 2015” yielded a most disappointing return, attracting some 35 votes at the Corby by-election in 2012.

He may yet prove to have been ahead of his time in that project, too.

More about

The IndependentA Clockwork OrangeChurch Of EnglandDaily TelegraphJoin our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments