- Home

Edition

Africa Australia Brasil Canada Canada (français) España Europe France Global Indonesia New Zealand United Kingdom United States Edition:

Global

Edition:

Global

- Africa

- Australia

- Brasil

- Canada

- Canada (français)

- España

- Europe

- France

- Indonesia

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- United States

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

Annie PM/Unsplash

How the internet became enshittified – and how we might be able to deshittify it

Published: December 3, 2025 6.36pm GMT

Charles Barbour, Western Sydney University

Annie PM/Unsplash

How the internet became enshittified – and how we might be able to deshittify it

Published: December 3, 2025 6.36pm GMT

Charles Barbour, Western Sydney University

Author

-

Charles Barbour

Charles Barbour

Associate Professor, Philosophy, Western Sydney University

Disclosure statement

Charles Barbour does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

Western Sydney University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

DOI

https://doi.org/10.64628/AA.ycqcy4wjn

https://theconversation.com/how-the-internet-became-enshittified-and-how-we-might-be-able-to-deshittify-it-269376 https://theconversation.com/how-the-internet-became-enshittified-and-how-we-might-be-able-to-deshittify-it-269376 Link copied Share articleShare article

Copy link Email Bluesky Facebook WhatsApp Messenger LinkedIn X (Twitter)Print article

Remember when Twitter used to be good? I reckon it peaked somewhere around the first COVID lockdowns.

In those days, there was a running gag on the site where everyone would refer to it as a “hellscape”. And it did invite some of the worst that humanity has to offer. Opinions, as the old joke goes, are like assholes: everybody has one.

But if you curated your Twitter feed effectively, you could have immediate scrolling access to the best journalism and cultural commentary, excellent podcasts and comedians, film criticism and book reviews, the latest trends in food, music or clothing, decent information about public health, live stream feeds of smart people on the ground at the most pressing events of the day, not to mention the wisecracks and insights of your friends.

It was like being perpetually part of an in-crowd. The promise of a world where potentially anyone could feel connected, in touch, popular.

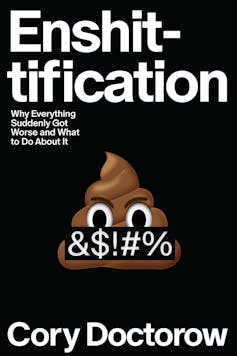

Review: Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It – Cory Doctorow (Verso)

Then came the rumours that the increasingly fascist-curious Elon Musk was scheming to buy the platform. Not possible, we thought at first. It would be a terrible business decision. And anyone interesting or important would flee overnight.

Then Musk did buy Twitter, horribly rebranding it as X. Then we speculated (or hoped) it would drive him bankrupt. Then it didn’t. Then, through deliberate and explicit effort, it went to shit.

Musk decided he would raise money by selling the coveted blue-checks, a form of authentication previously reserved for those who had developed their influence organically. He changed the algorithm to reflect his own views and fired moderators tasked with weeding out misinformation and hate speech. As a result, the platform formerly known as Twitter was soon full of ads, gore, porn, toxicity, AI slop and scams of all variety.

Yet, as if trapped by their established followings or perhaps some contagious fear of missing out, people stayed. Calls to migrate en masse to other liberal-coded platforms largely failed.

For some reason, this logic seems to be taking over all social media, even the internet itself. Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Amazon, Google, Apple, Uber, Spotify: everything turns to shit. And no one is able to escape.

To paraphrase a song about another way we get trapped by misplaced desires: welcome to the Hotel Crapifornia. You can check in any time you like, but you can never leave.

An inhuman nightmare

In 2022, Canadian journalist, novelist and activist Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” to describe the degeneration of the internet.

Back when the internet was good, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Doctorow was every hipster’s hero. His blog Boing Boing was required reading for anyone interested in emerging technologies. If you wanted to be recognised as cool, you entered the coffee shop conspicuously carrying a copy of his latest book. It seemed that no one knew more about where technology had come from, and where it was likely to go. He was our prophet.

His 2003 novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, for example, was a dystopian story of a post-scarcity world where monetary currency had been replaced with what Doctorow called “whuffie” – essentially a measure of how much others respect you.

This was just before social media stormed into all our lives, with its vertiginous economy of likes and followers, attention and influence.

All these years later, Doctorow’s Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It is an attempt to explain how the great dream of the internet – its powerful democratising potential, its incredible capacity to generate human communities and circulate human knowledge – turned into an inhuman nightmare.

We were offered a world of connection and cooperation – an open-source paradise of instant and free access, liberated from the fetters of both corporate ownership and state control.

What we got was a world of ruthless monopolies and oligarchs who control a colossal surveillance apparatus capable of tracking our most private behaviours, producing a population of powerless, compliant consumers – people who have no choice but to keep using their abysmally bad products, because there is nowhere else to go.

Prisoners of our own devices

“Enshittification” is not just a clever term for the grumpy complaint of an ageing Gen-X tech-head. Doctorow wants to develop it as a formal concept that explains the process by which internet platforms, applications and innovations go from being loved by their users to being despised.

Beginning with the case studies of Facebook, Amazon and the iPhone, then expanding out to more or less every platform on the internet, Doctorow proposes that enshittification has three basic stages.

First, platforms are good to their users. People genuinely want to participate. A community develops, but not much profit is made.

Second, in an effort to monetise this new community, platforms are good to companies. They offer them access to markets through advertising or shipping or proprietary arrangements.

Finally, they find a way to screw over those business customers as well as their users to claw all excess value back for themselves.

That is how we arrived at what Doctorow calls “a giant pile of shit”.

Amazon is the easiest example to explain. It started by providing a service that people wanted: fast cheap delivery of products. It then attracted business customers by providing a means to increase profit and market share.

But then, like a medieval warlord, it crushed all competition and used its market dominance to compel tributes from its business customers, in the form of fees that absorbed and exceeded whatever extra profit they may have made in the first place.

At this point, Amazon has absolutely no reason to improve its service. In fact, in order to siphon off even more value by cutting costs, it has every reason to make its service worse.

For Doctorow, the problem is not that some or many internet platforms follow this kind of enshittifying procedure; it is that almost all of them do. And given the ubiquity of the internet in our daily lives, particularly with the advent of the smartphone, our entire world has become enshittified.

We are now in what Doctorow calls the “enshittoscene”. To return to the musical reference mentioned above: we are all just prisoners here, of our own devices.

Cory Doctorow coined the term ‘enshittification’ in 2022.

Internet Archive, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Cory Doctorow coined the term ‘enshittification’ in 2022.

Internet Archive, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Make the internet good again

As Doctorow notes, it is easy to predict how the tiny handful of ghouls who benefit from this situation are likely to respond. Well, they are going to say, it might not be great, but that’s capitalism. And as everyone knows, capitalism is the worst system, except for all the others.

But Doctorow refuses to accept the familiar neoliberal logic of “there is no alternative”, because members of his generation (which also happens to be mine) know this is a sham. We know there is an alternative, because we have seen it with our own eyes. The internet was not always shit. It used to be good. And it could be good again.

Doctorow’s proposals for recreating a good internet – one that combines the autonomy and choice of the old internet with the mass scale of the current shit internet – are fourfold: competition, regulation, interoperability and tech-worker power.

In the first instance, Doctorow insists that the internet today is not capitalist at all. Following the economist Yanis Varoufakis, he calls it “technofeudalist”. Like medieval landlords, the tech overlords don’t make money in the enshittoscene by creating or circulating new products. They make it by owning the platforms for the creation or circulation of products and compelling everyone else to rent space on those platforms.

Smashing these rentier monopolies and opening spaces for healthy competition is step one. But doing so will require robust antitrust regulations, which can break the near-monopolies enjoyed by tech companies like Google and prevent anti-competitive corporate mergers. Avenues for enshittification must be shut down by law and this must be coordinated at an international level.

These laws must guarantee the interoperability of all technological systems. Currently, one of the most expensive fluids on planet earth is HP printer ink. HP sets the price unilaterally, because they construct their printers so that no other ink cartridges will work.

In the enshittoscene, the principle of anti-interoperability spreads across nearly all platforms and products. But regulation could ensure that all technological operating systems are compatible with one another, just as regulation ensures that household electronic devices are compatible with uniform powerpoints.

Finally, and most importantly, the people who work in tech industries can be empowered to realise the ethos of collaboration and innovation that, by and large, they share. For the truth is, Doctorow suggests, that most of the people who actually do the work in the enshittoscene – those who build and manage the platforms – hate it as much as the users do. And empowering them would go a long way towards empowering all of us.

- Social media

- Internet

- Book reviews

- Enshittification

Events

Jobs

-

Respect and Safety Project Manager

Respect and Safety Project Manager

-

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

-

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

-

University Lecturer in Early Childhood Education

-

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting

- Editorial Policies

- Community standards

- Republishing guidelines

- Analytics

- Our feeds

- Get newsletter

- Who we are

- Our charter

- Our team

- Partners and funders

- Resource for media

- Contact us

-

-

-

-

Copyright © 2010–2025, The Conversation

Respect and Safety Project Manager

Respect and Safety Project Manager

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

Associate Dean, School of Information Technology and Creative Computing | SAE University College

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Senior Lecturer, Clinical Psychology

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting

Case Specialist, Student Information and Regulatory Reporting