These two designs represent artist concepts for the potential look and architecture of the upcoming, planned NASA astrophysics flagship mission of HWO: the Habitable Worlds Observatory. It will represent a truly generational leap, the same way Hubble or JWST did for NASA science. As the #1 recommended mission by the National Academy of Sciences’ 2020 decadal survey, it will be the first mission to directly image Earth-sized worlds at Earth-like distances around Sun-like stars, but only if we design, advance, fund, and build it, along with the full relevant suite of instruments.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

Key Takeaways

These two designs represent artist concepts for the potential look and architecture of the upcoming, planned NASA astrophysics flagship mission of HWO: the Habitable Worlds Observatory. It will represent a truly generational leap, the same way Hubble or JWST did for NASA science. As the #1 recommended mission by the National Academy of Sciences’ 2020 decadal survey, it will be the first mission to directly image Earth-sized worlds at Earth-like distances around Sun-like stars, but only if we design, advance, fund, and build it, along with the full relevant suite of instruments.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

Key Takeaways

- In the search for life beyond Earth, we can directly probe what’s right here in our Solar System or listen for intelligent civilizations, but most inhabited planets will require us to find and detect any life on them remotely.

- NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory should make that possible, but only if the associated technologies, including an all-important coronagraph, can reach an unprecedented sensitivity.

- Their next upcoming flagship mission, however, the Nancy Grace Roman space telescope, can demonstrate progress toward those coronagraphic capabilities. With a new discovery by the Subaru telescope, the best-ever target just appeared.

For as long as humanity has been looking up at the heavens, we’ve been pondering some of the biggest questions of all. It’s only over the past few hundred years that science has caught up to our vast imaginations, and has begun answering those questions for the first time in our civilization’s history. We know what the stars are: they’re much like our own Sun, except very far away. We know that the majority of them have planets, and that some of those planets are Earth-sized. We know that those worlds are composed of very similar ingredients to our own Solar System’s planets, and that they are governed by the same underlying laws of nature.

But are any of those worlds actually inhabited?

Here, as the end of 2025 approaches, that’s still a great cosmic unknown. We don’t yet know whether we’re alone in the Universe or not, and if not, how common or rare life actually is. While we can send orbiters, landers, and rovers to worlds within our Solar System and scan the skies for signals that might arise from intelligent extraterrestrials, finding most instances of life in the Universe will require scanning exoplanets directly to probe for biosignatures. That’s the ambitious science goal of the #1 ranked future NASA mission: the Habitable Worlds Observatory, which seeks to directly image:

- Earth-sized planets,

- at Earth-like distances,

- around Sun-like stars.

Will we be able to get there? That all depends on how good our ever-improving coronagraph technology will be. With the new discovery of stellar companion HIP 71618 B, just announced in early December of 2025, we’re definitively going to get to put our best efforts so far to the critical test. The ability to find our first “alien Earth” hinges on the outcome.

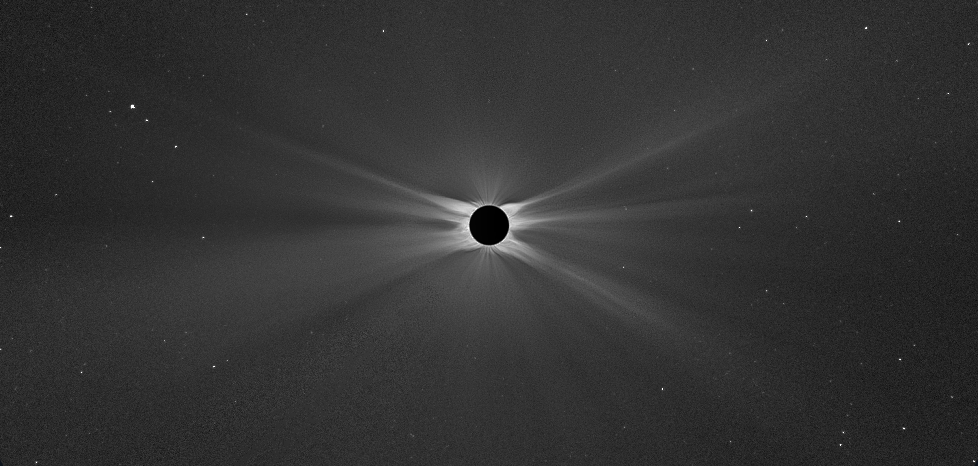

The solar corona, as shown here, is imaged out to 25 solar radii during the 2006 total solar eclipse. The longer the duration of a total solar eclipse, the darker the sky becomes, and the better the corona and background astronomical objects can be seen. Experienced, serious eclipse photographers can construct images such as these from their eclipse data, showcasing the extent of the solar corona as well as a plethora of more distant background astronomical objects.

Credit: Martin Antoš, Hana Druckmüllerová, Miloslav Druckmüller

The solar corona, as shown here, is imaged out to 25 solar radii during the 2006 total solar eclipse. The longer the duration of a total solar eclipse, the darker the sky becomes, and the better the corona and background astronomical objects can be seen. Experienced, serious eclipse photographers can construct images such as these from their eclipse data, showcasing the extent of the solar corona as well as a plethora of more distant background astronomical objects.

Credit: Martin Antoš, Hana Druckmüllerová, Miloslav Druckmüller

It isn’t necessarily obvious how these different pieces of the scientific story are related to each other, so let’s explain. A coronagraph is a relatively simple piece of equipment, based on a simple concept that we experience naturally here on Earth: a total solar eclipse. Celestially, a total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes in front of the Sun relative to our line-of-sight here on Earth. However, there’s a catch: the Moon needs to appear large enough, in terms of angular size, to block out the entirety of the Sun’s disk. When this alignment properly occurs, and you stand in the eclipse shadow on Earth, the Sun’s light is entirely blocked, and you can see all sorts of sights that would otherwise be washed out: the solar corona, the stars that lie behind the Sun, satellites, and more.

What makes a coronagraph different is that instead of blocking out the light from our close, nearby Sun, it places a small obstacle (usually a disk) in front of the telescope’s lens, blocking out the light from an ultra-distant star. By having the coronagraph block only the light from the disk of the star, all sorts of features that are present around the star, even if faint, can then be revealed. Although many telescopes had leveraged coronagraphs throughout the 20th century, there was a real revolution when we launched the Hubble Space Telescope equipped with a coronagraph. For the first time, incredible features could be seen: debris disks, protoplanetary disks, and even full-fledged planets around other stars.

This two-panel view of the debris disk around Vega shows Hubble’s (left) and JWST’s (right) views, respectively. Hubble reveals a wide disk of dust, showcasing particles approximately the size of smoke particles, while JWST shows the glow of warm (larger-sized) dust particles distributed throughout the Vega system, with only one small dip in brightness at double the Sun-Neptune distance. JWST’s coronagraph is approximately 100 times more sensitive than Hubble’s.

This two-panel view of the debris disk around Vega shows Hubble’s (left) and JWST’s (right) views, respectively. Hubble reveals a wide disk of dust, showcasing particles approximately the size of smoke particles, while JWST shows the glow of warm (larger-sized) dust particles distributed throughout the Vega system, with only one small dip in brightness at double the Sun-Neptune distance. JWST’s coronagraph is approximately 100 times more sensitive than Hubble’s.Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, S. Wolff (University of Arizona), K. Su (University of Arizona), A. Gáspár (University of Arizona)

As remarkable as Hubble’s coronagraph was, however, it was still severely limited. It was only capable of observing:

- the intrinsically brightest features,

- at the greatest angular separations,

- from the closest stars,

as seen from Earth. In terms of optical performance, what we often talk about in the science of coronagraphy is known as contrast. Contrast, in this context, is how faint an object can intrinsically be — relative to the bright object being blocked by the coronagraph — and still be detected, resolved, and measured by the instrument.

For Hubble, it was a huge revolution. We discovered debris disks for the first time, we obtained our first direct images of exoplanets, and we could detect faint companions — including brown dwarfs — in places we didn’t even necessarily expect to find them. But we couldn’t see small planets, or planets close to their parent stars, or planets around faint, low-mass stars, for an important reason: Hubble’s coronagraphic contrast was only at about the 1-part-in-1000 (or 10-3) level, meaning that an object needed to be at least 0.1% intrinsically as bright as the star the coronagraph was blocking in order to be seen by Hubble.

This view of the Fomalhaut system consists of mid-infrared JWST data (in yellow) overlaid with radio (red) ALMA data and blue (optical/UV) Hubble data. Only JWST is capable of revealing the inner structure of this system, including a large inner disk and a surprising intermediate belt: features only able to be seen at long wavelengths of light due to their incredibly cool temperatures.

Credit: Adam Block/Andras Gaspar/Steward Observatory/University of Arizona

This view of the Fomalhaut system consists of mid-infrared JWST data (in yellow) overlaid with radio (red) ALMA data and blue (optical/UV) Hubble data. Only JWST is capable of revealing the inner structure of this system, including a large inner disk and a surprising intermediate belt: features only able to be seen at long wavelengths of light due to their incredibly cool temperatures.

Credit: Adam Block/Andras Gaspar/Steward Observatory/University of Arizona

With the launch of JWST, however, its next-generation coronagraph provided an enormous improvement. Instead of contrasts of 10-3, its coronagraph achieves contrasts that are improved by nearly a factor of 100 over Hubble’s: contrasts of more like 10-5. As you can see, above, this has enabled us to find features that are much more profound, faint, and require much greater sensitivity than anything Hubble is capable of detecting. Instead of just protoplanetary and debris disks, it could see features in those disks, including rings, gaps, and belts. Instead of just brown dwarfs, it could find Jupiter-sized and even Neptune-sized planets around dim stars. It could find planets closer in to their parent star than Hubble could, and its groundbreaking discoveries are still rolling in even today.

But JWST’s coronagraph’s contrast, even though it can resolve features that are a factor of 100,000 fainter than the parent star that it blocks, doesn’t get us close to reaching our main goal: of directly imaging Earth-sized planets at Earth-like orbital distances from Sun-like stars, and of doing it at optical (i.e., visible light) wavelengths. This is extra problematic, because:

- planets are much fainter than stars,

- closer planets that are much smaller than their parent stars are the hardest to image,

- and planets are also much cooler than stars, meaning more of a planet’s light is at infrared, rather than at visible light, wavelengths.

JWST’s coronagraph is much more effective at imaging companion objects around stars in infrared wavelengths than it is at optical wavelengths, and even with a contrast of 1-part-in-100,000, it still has a long way to go to detect an Earth-like world, which would require a contrast of 10-10 or better.

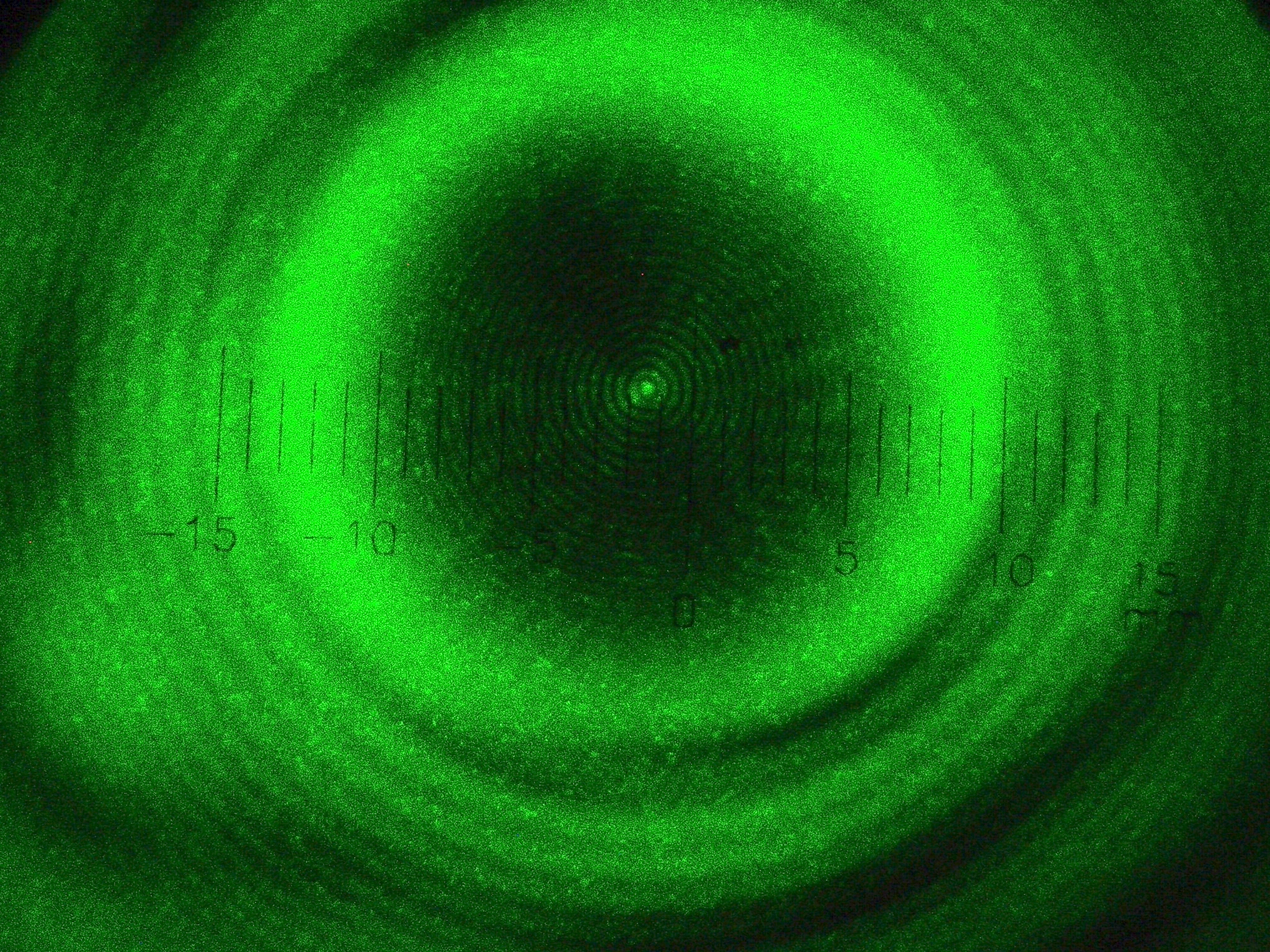

The results of an experiment, showcased using laser light shone around an object with a circular cross-section, in terms of the actual acquired optical data. Instead of a dark shadow with a solid light glow around it, we see a series of concentric rings inside the shadow as well as outside of it. This property of light, that it undergoes interference and diffraction, poses a difficulty for the simplest designs of a coronagraph, even for space telescopes.

The results of an experiment, showcased using laser light shone around an object with a circular cross-section, in terms of the actual acquired optical data. Instead of a dark shadow with a solid light glow around it, we see a series of concentric rings inside the shadow as well as outside of it. This property of light, that it undergoes interference and diffraction, poses a difficulty for the simplest designs of a coronagraph, even for space telescopes.Credit: Thomas Bauer/Wellesley

This is kind of an annoying problem for astronomers, as it is for anyone who deals with optical systems. As you can see, as shown above, if you place a perfectly disk-like object (a solid circle, a sphere, a face-on cylinder, etc.) in front of a light source, you won’t just see all of the light that goes around the disk, counterbalanced by a perfect silhouette of the disk itself in shadow. Instead, because light is a wave, you see evidence for the phenomena of interference and diffraction. In particular, there will be a bright spot at the center of the shadow (enveloped by fainter, concentric rings) accompanied by bright rings of light that show up on the outside of the disk’s shadow.

This limits the maximum coronagraphic contrast you can achieve with simply a circular disk to about 10-6, even with optically ideal materials. Does this mean that the dream of detecting Earth-sized worlds at Earth-like distances from Sun-like stars with a coronagraph is impossible?

No, not necessarily. What it means is that we have to develop better coronagraphic technologies than what’s achievable with the “simple optical disk” configuration. There’s an incredible amount of science that goes into this — most of which is being conducted at federally funded US institutions like the Space Telescope Science Institute, NASA’s Goddard and Ames, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Caltech, plus the University of Arizona — but the general approach is to introduce a segmented coronagraph design. There’s a roadmap for how we’re going to do this, and we’ve already come so far as we prepare for the launch of NASA’s next flagship mission: the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope.

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman telescope has completed construction and is nearly ready for launch. Its instrument suite, including its coronagraph, represents the cutting-edge of instrumentation in astronomy, and should pave the way for even further improved technology aboard the future Habitable Worlds Observatory: enabling the direct imaging of potentially Earth-like planets. At the end of 2025, however, it remains to be seen whether this new, completed flagship observatory will even be launched in 2026, as the scheduled funding allotted to the endeavor is less than the cost of a launch.

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman telescope has completed construction and is nearly ready for launch. Its instrument suite, including its coronagraph, represents the cutting-edge of instrumentation in astronomy, and should pave the way for even further improved technology aboard the future Habitable Worlds Observatory: enabling the direct imaging of potentially Earth-like planets. At the end of 2025, however, it remains to be seen whether this new, completed flagship observatory will even be launched in 2026, as the scheduled funding allotted to the endeavor is less than the cost of a launch.Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn

For many years, astronomers focused on instrumentation have been working to improve the capabilities of a coronagraph: particularly one that goes onto a space telescope. The ultimate goal — a goal put forth for the Habitable Worlds Observatory, slated to be the next flagship mission for NASA astrophysics after the already-completed Nancy Grace Roman observatory launches — is to not only achieve that vaunted brightness contrast of 10-10, but to get there at optical, visible light wavelengths. The state-of-the-art coronagraph (the best ever, by far) on board the Nancy Grace Roman telescope should represent an enormous step in that direction: to contrasts of at least 10-7 but that could go as high as 10-9, which is an enormous leap over all prior observatories.

At least, that’s how the Roman coronagraph is expected to perform, based on laboratory tests. But how will it perform when it’s actually in space, attached to the telescope, and observing a target of interest in the wavelength range (i.e., the optical) of interest?

In order to find out, we need to have an appropriate target. That means an astronomical target where:

- the separation between the main star and the secondary object is between 0.15″ and 0.45″, where an arc-second (denoted by “) is 1/3600th of a degree,

- where the secondary object is no more than one ten-millionth (10-7) as bright as the primary object,

- at a wavelength of less than 600 nanometers.

In this scenario, such a system would enable Roman to achieve a 5-σ significance (the gold standard for “discovery”) detection of the secondary object in under 10 hours of imaging.

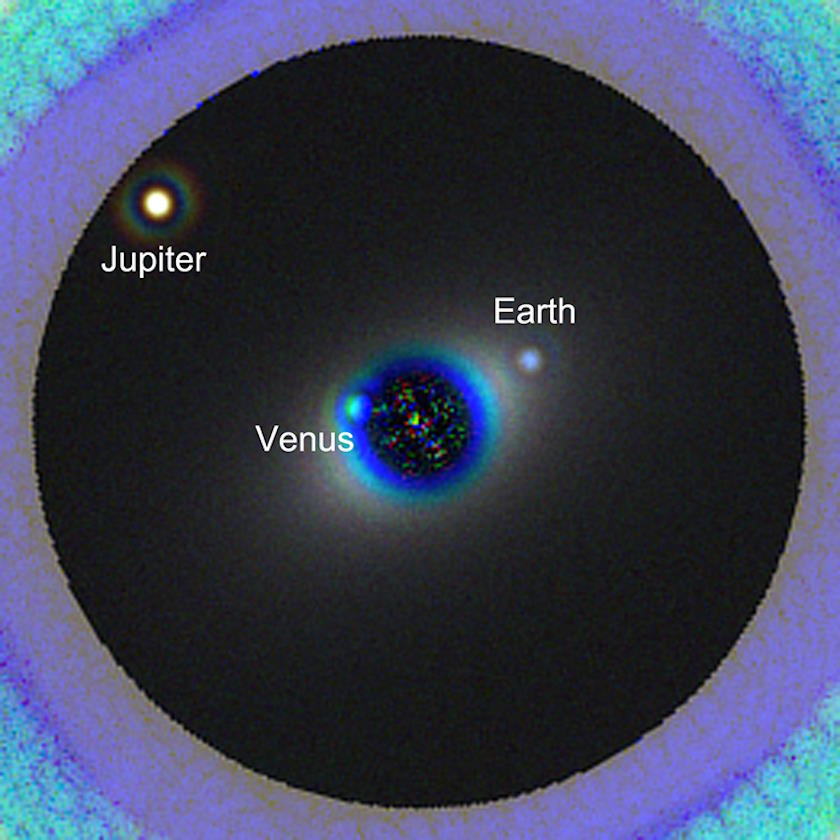

If the Sun were located at the distance of Alpha Centauri, the future Habitable Worlds Observatory, either with a starshade or a sufficiently advanced coronagraph, would not only be able to directly image Jupiter and Earth, including taking their spectra, but even the planet Venus as well. The farther out giant planets, including Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, would all be perceptible as well.

Credit: L. Pueyo, M. N’Diaye (STScI)

If the Sun were located at the distance of Alpha Centauri, the future Habitable Worlds Observatory, either with a starshade or a sufficiently advanced coronagraph, would not only be able to directly image Jupiter and Earth, including taking their spectra, but even the planet Venus as well. The farther out giant planets, including Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, would all be perceptible as well.

Credit: L. Pueyo, M. N’Diaye (STScI)

That’s where the new research comes in, and what makes it so exciting: for the first time, a naturally occurring astronomical system that actually meets all of these parameters has been discovered! The key to discovering it took many steps, many years of work, and — most importantly — a variety of powerful astronomical facilities in order for it to be possible.

First, you have to use astrometry, or the science of tracking a star’s position and motion over time, to show that it isn’t just moving through space, but is “wobbling” or spiraling as it moves. With satellites like Hipparcos in the 20th century and now Gaia here in the 21st, we’ve measured the precise positions and motions of more than a billion stars within the Milky Way. Pulling out the candidate stars with motions consistent with the presence of a massive object (e.g., a massive planet or brown dwarf) at the right separation distance for these observations is the first step: not from their radial velocity, but from their observed motions, which indicate relatively face-on systems.

Next, you want to use a flagship-class ground-based telescope — one outfitted with a coronagraph, adaptive optics technology, and infrared observing capabilities — to acquire deep images of the system, with the parent star blocked by the coronagraph, at long wavelengths and at multiple different points in time. Sometimes, you’ll find a bright object: a companion star. Other times, you’ll find nothing: if there is a secondary, it might be too faint to see. But when the system is just right, you’ll find a faint, sub-stellar secondary companion, and that’s the sweet spot.

And finally, when the Nancy Grace Roman telescope launches, it can observe that target with its coronagraph at the proper wavelength and for the right duration, enabling us to field-test our progress toward the ultimate goal (of finding an inhabited, Earth-like world) and test our true coronagraphic capabilities.

This animation shows the discovery images of the super-Jupiter exoplanet HIP 54515 B, of approximately 18 Jupiter masses at a distance of 25 AU from its parent star. This planet, discovered in 2025, marks only the third exoplanet ever discovered through astrometry.

Credit: T. Currie & Li et al., Astronomical Journal, 2025

This animation shows the discovery images of the super-Jupiter exoplanet HIP 54515 B, of approximately 18 Jupiter masses at a distance of 25 AU from its parent star. This planet, discovered in 2025, marks only the third exoplanet ever discovered through astrometry.

Credit: T. Currie & Li et al., Astronomical Journal, 2025

It’s only recently that we’ve been able to use the first two steps of this method to actually find objects that are smaller and fainter than their parent stars but that orbit around them. In fact, the first giant planets that were discovered as a result of using ground-based follow-ups to initial astrometry data were only announced in 2023: by a team led by astronomer Thayne Currie. In the time since, Currie’s group at the University of Texas at San Antonio — in collaboration with many others — has revealed another systems with a super-Jupiter planet: a remarkable advance in its own right, bringing the total number of such planets found with astrometry and confirmed with follow-up imaging to three.

However, that same collaboration, using the same method, has now just revealed a system where a brown dwarf (or a “failed star”) orbits its bright, more massive companion with precisely the right properties to field-test the Roman coronagraph.

That system turns out to be the star 33 Boötes (also known as HIP 71618), located 188 light-years away. The star is bigger than the Sun (about 2.25 solar masses), significantly brighter than the Sun (around 20 times brighter), and younger than the Sun as well (at just 142 million years). However, the astrometry data indicated that it might have a stellar companion, and a combination of Keck Observatory imaging data and data from the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics (SCExAO) system was able to reveal the nature and properties of that secondary companion exquisitely.

These five separate panels show five different images, all assembled from Subaru (SCExAO/CHARIS) and Keck (KECK/NIRC2) ground-based telescope data acquired with coronagraphs. Although these images were all acquired at long, infrared wavelengths, they enable us to infer what would be visible at optical wavelengths.

Credit: M. El Morsy et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

These five separate panels show five different images, all assembled from Subaru (SCExAO/CHARIS) and Keck (KECK/NIRC2) ground-based telescope data acquired with coronagraphs. Although these images were all acquired at long, infrared wavelengths, they enable us to infer what would be visible at optical wavelengths.

Credit: M. El Morsy et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

The secondary, now known as HIP 71618 B, is:

- a brown dwarf,

- separated by around 0.3″ from its primary,

- on an elliptical orbit (so that the distance from the secondary to the primary changes over time),

- and is clearly detectable with ground-based telescopes at infrared wavelengths.

The imaging data allows us to fit an orbit to the system, and tells us that when the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is ready to test its coronagraphic capabilities (during the first half of 2027), the system will be separated by between 0.25″ and 0.27″: right in the sweet spot for proving the coronagraphic technology’s capabilities. Because brown dwarfs are so much cooler and fainter than bright, massive stars, however, we need much more contrast in the optical (and far superior coronagraphy) than we require in the infrared (which is accessible with our ground-based telescopes).

It’s not necessarily surprising or groundbreaking to find a brown dwarf orbiting a star more massive than the Sun at the same distance that our gas giant planets orbit our Sun. However, finding a system that can put the Roman coronagraph to this key test — where it can prove that our coronagraphic capabilities are on the right track to image Earth-sized worlds at Earth-like distances around Sun-like stars — is truly revolutionary. As lead author of the discovery study, Mona El Morsy, put it:

“The HIP 71618 system checks off the boxes for what we need for the technology demonstration. Its star is suitably bright. Its companion HIP 71618 B is located within a region where these new technologies from Roman will work. At the wavelengths where the Roman Coronagraph will operate, we predict that HIP 71618 B will be faint enough compared to its host star that a strong detection with Roman will validate these technologies.”

In order to demonstrate the appropriate coronagraphic contrast needed to validate our progress toward imaging an Earth-sized planet at Earth-like distances around Sun-like stars, we need a system with the right separation between primary and secondary components, along the right brightness ratios in the right wavelength range. HIP 71618 B is the first known system to meet all of the necessary parameters.

Credit: M. El Morsy et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

In order to demonstrate the appropriate coronagraphic contrast needed to validate our progress toward imaging an Earth-sized planet at Earth-like distances around Sun-like stars, we need a system with the right separation between primary and secondary components, along the right brightness ratios in the right wavelength range. HIP 71618 B is the first known system to meet all of the necessary parameters.

Credit: M. El Morsy et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

This system, to be blunt, is exactly what we’ve been waiting for. It’s not the only system that will be interesting for Roman to image with its coronagraph, and it’s definitely not a unique system out there in the galaxy or the Universe. Rather, it’s the first key example of a system that can be used for testing, proving, and honing the coronagraphic imaging technologies that are needed to detect, image, and characterize our first “exo-Earths” in the future.

With each major observatory that we design, build, calibrate, commission, and use, we don’t just gain the scientific knowledge that arises from the data we collect, although we certainly have gained so much knowledge from Hipparcos, Gaia, Keck, Subaru, Hubble, JWST, and will certainly gain a prodigious amount from Roman as well. In addition, we:

- gain the ability for these very different observatories (with different strengths, sensitivities, and capabilities) to work together to learn more about the Universe, including from in space as well as on the ground,

- and gain the technological expertise we need to enable the future observatories, instruments, and technologies that can help us achieve future goals in science and beyond.

We have the instruments, we have the laboratory infrastructure, we have the facilities, and we have the expertise. The big, ultimate science goal of imaging “alien Earths” is within reach, and all we have to do is continue investing in the roadmap that’s brought us to this point. Learning the answer to perhaps the biggest existential question in the Universe — the question of “Are we alone?” — depends on it.

The author acknowledges Thayne Currie for useful communication regarding these results.

Tags Space & Astrophysics In this article Space & Astrophysics Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all. Subscribe