It’s a striking contradiction: Four Black American artists get major shows in Europe while the American institutional capacity and constitutional protections collapse in tandem.

Leilani Lewis

November 30, 2025

— 5 min read

Leilani Lewis

November 30, 2025

— 5 min read

Nina Chanel Abney's opening reception at Elbow Church in Amersfoort, Netherlands, in September (photo Leilani Lewis/Hyperallergic)

Nina Chanel Abney's opening reception at Elbow Church in Amersfoort, Netherlands, in September (photo Leilani Lewis/Hyperallergic)

Something shifted the moment I stood inside the Elbow Church art space in Amersfoort in the Netherlands this past September. As journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones delivered a sharp lecture beneath Nina Chanel Abney's monumental installations, it became clear that this Medieval city was presenting narratives of Black American life that the United States is increasingly unwilling to hold. Jacob Lawrence: African American Modernist and Nina Chanel Abney: Heaven's Hotline opened in Amersfoort on the same evening. Together, Lawrence's historical narratives and Abney's bold indictments mapped the breadth of Black American artistic vision in a way that felt both clarifying and impossible to ignore.

In fact, this year, four major European museums simultaneously staged ambitious exhibitions of Black American artists: Kerry James Marshall at London's Royal Academy, Lawrence at Kunsthal KAdé in Amersfoort, Abney in Paris and Amersfoort, and Mickalene Thomas at Les Abattoirs in Toulouse and forthcoming at the Grand Palais in Paris, all shows I visited with the exception of the first. This moment feels less like a coincidence and more like a long-overdue reckoning.

Visitor looking at Augusta Savage's bronze cast of "Gwendolyn Knight" (1935) in Jacob Lawrence: African American Modernist at Kunsthal KAdé (photo © Mike Bink; image courtesy Kunsthal KAdé)

Visitor looking at Augusta Savage's bronze cast of "Gwendolyn Knight" (1935) in Jacob Lawrence: African American Modernist at Kunsthal KAdé (photo © Mike Bink; image courtesy Kunsthal KAdé)These are not demure gallery shows. They are massive institutional commitments — entire floors and, in some cases, entire museums devoted to a single artist with hundreds of works spanning decades. These shows refuse simplification as they document Black American life, histories, love, resistance, queerness, labor, death, and joy without apology or translation.

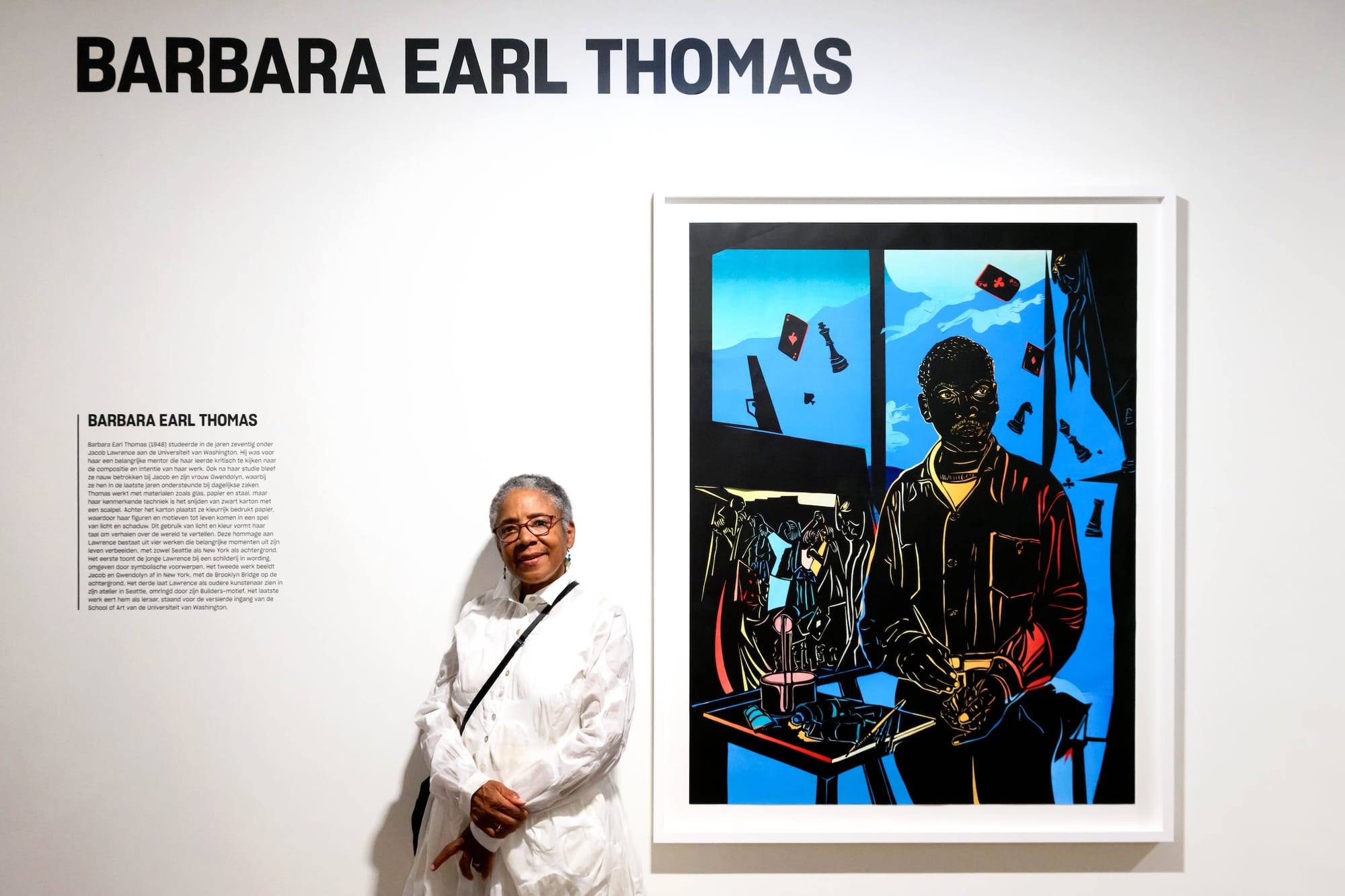

At Kunsthal KAdé, Dutch audiences are encountering Jacob Lawrence in his first European overview. The museum also commissioned four new portraits of Lawrence by contemporary artist Barbara Earl Thomas, his friend and former student at the University of Washington in Seattle.

It's a striking contradiction: These groundbreaking shows and unprecedented opportunities for iconic Black American artists in Europe come at the exact moment that American institutional capacity, social infrastructure, and constitutional protections are collapsing in tandem.

Jacob Lawrence, Genesis series (1989), silkscreen prints, at the Kunsthal KAdé in Amersfoort, Netherlands (photo © Mike Bink; image courtesy Kunsthal KAdé)

Jacob Lawrence, Genesis series (1989), silkscreen prints, at the Kunsthal KAdé in Amersfoort, Netherlands (photo © Mike Bink; image courtesy Kunsthal KAdé)In July, Amy Sherald withdrew her exhibition American Sublime from the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery after it reportedly deemed her painting of a Black transgender woman as the Statue of Liberty too controversial. And according to the American Alliance of Museums, one-third of museums in the United States have lost federal funding since Trump took office, with around one in four slashing programs for underserved communities.

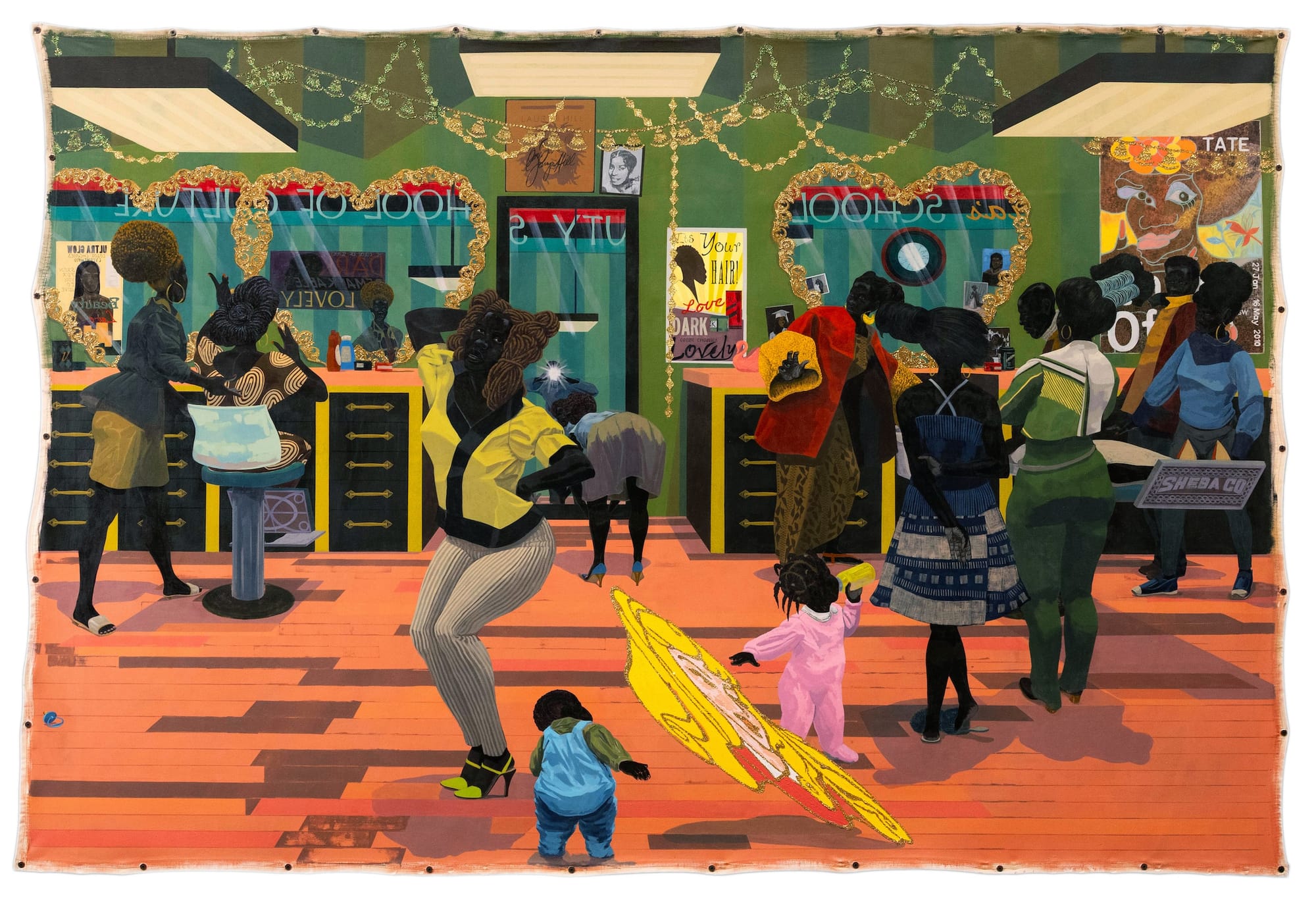

It's within this climate of censorship, disinvestment, and erasure at home that Kerry James Marshall's exhibition at the Royal Academy in London takes on even sharper resonance. Here, Marshall mounted the largest survey of his work ever presented in Europe, filling over a thousand square meters with more than 70 artworks and insisting that Black presence belongs at the center of Western art history. His monumental paintings, such as “School of Beauty, School of Culture” (2012), assert visibility and permanence even as people vanish from American communities, some violently removed by ICE raids, others quietly deported without notice or warning, all without constitutional protection.

Kerry James Marshall, "School of Beauty, School of Culture" (2012), acrylic on canvas (image courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

Kerry James Marshall, "School of Beauty, School of Culture" (2012), acrylic on canvas (image courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)Mickalene Thomas's exhibitions in Europe are equally canon-shifting. All About Love at Les Abbatoirs in Toulouse was her first major show in France, and she will break yet another barrier in December by opening the first-ever major exhibition by an African-American artist at the Grand Palais in Paris. Her striking rhinestone portraits of Black women — like “Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe: Les trois femmes noires” (2010) and “Afro Goddess Looking Forward” (2015) — radiate glamor, intellect, and authority on a scale historically rare in major French institutions. European audiences embraced Thomas's All About Love, while over 300,000 Black women in the United States were pushed out of the workforce this year and their unemployment rate climbed to 6.7% in August as federal and corporate layoffs systematically targeted positions many had long held, including in dismantled Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion programs.

Abney's Heaven's Hotline in the Elbow Church confronts religious capitalism and American Christian ideals with her monumental sculptures, even as White Christian nationalism in the United States becomes more extreme and entrenched.

Across Europe, these exhibitions offer Black American stories that subvert reductive narratives. These artists speak for themselves, asserting specificity, imagination, and a refusal to be flattened or erased. Yet, these contradictions expose something larger than a funding crisis or political cycle. They reveal a nation fractured into competing narratives and a fight over whose stories prevail.

Barbara Earl Thomas with her linocut "Jacob as a Young Artist" (2025) in Jacob Lawrence: African American Modernistat London's Royal Academy (photo © Mike Bink; image courtesy Kunsthal KAdé)

Barbara Earl Thomas with her linocut "Jacob as a Young Artist" (2025) in Jacob Lawrence: African American Modernistat London's Royal Academy (photo © Mike Bink; image courtesy Kunsthal KAdé)Black Americans seeking and receiving better recognition in Europe is not new. James Baldwin, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Richard Wright, and many others sought reprieve there while white supremacy raged on at home. But this moment transcends individual refuge. Major European institutions are making visible, well-funded commitments to Black American narratives as the United States is seeking to neutralize, and tame what is evidenced in their power and skill.

Walking through the exhibitions this fall, I felt the rupture between the full, complex realities of Black American experiences that these artists confront — erasure, exclusion, brutality, but also joy, resistance, and refusal — and the containment efforts happening at home. And I found myself wondering what European audiences make of seeing both sides of this growing chasm at once.

A precedent is being set right now about which American stories are carried forward. Who steps up to witness matters. Who remembers matters. And who looks away will be remembered, too.